May 10, 2024

What Is Wayfinding?

May 10, 2024

As you can see, the answer can be quite complex. In short, we can define wayfinding as a system of elements working together to provide clarity and assistance to people in the built environment. The goal of any wayfinding design system should be to aid the user in orienting themselves in a space and then in navigating to a specific destination. It is like breadcrumbs that may help us find our way back to where we began our journey.

Want to learn more? At RSM Design, we are passionate about wayfinding, as well as its various models, components, and applications. With a comprehensive and evolving wayfinding definition, we are able to discover the unique potential of any environment. Keep reading about how we define wayfinding below, learn more about our wayfinding services, or contact us to start a conversation.

How do various dictionaries and other authorities define wayfinding? Looking at these definitions demonstrates how difficult it is to accurately define this term.

The Society for Experiential Graphic Design, or SEGD, says, “Wayfinding refers to information systems that guide people through a physical environment and enhance their understanding and experience of the space.”

Historically, this has been the role of signage, and many people think of wayfinding and signage as synonymous. But wayfinding should be considered in all the disciplines—architecture, interiors, landscape, lighting, and, yes, signage and graphics.

According to Wikipedia, wayfinding “encompasses all of the ways in which people (and animals) orient themselves in physical space and navigate from place to place.”

While this offers us a much broader definition, it may be too broad for our purposes. Instead, we are focused on how human beings use wayfinding, rather than all creatures.

Tellingly, neither Dictionary.com nor Webster’s dictionary list “wayfinding” as a known term.

To gain a better understanding of what wayfinding really means, let us examine how it has been used both historically and in the present day.

Have you ever wondered, “What is wayfinding like in practice?” If so, taking a look at how past societies have oriented themselves and navigated can help shape a more practical wayfinding definition.

In Polynesian cultures, for instance, wayfinding meant navigating the open ocean by careful observation of the stars and planets. National Geographic describes how, with these few consistent and organized cues from the environment, the Polynesians were able to successfully navigate thousands of miles of the Pacific Ocean long before the existence of GPS or even maps.

The celestial bodies and their relationship to Earth was decoded by these ancient wayfarers, who then used their knowledge to navigate an unforgiving environment where getting lost carried with it the ultimate consequence. Theirs was a situation in which safety (and the ability to return to land) was paramount—the fundamental purpose of wayfinding was safety, which brought with it the confidence to venture out—to leave the island in search of something more.

Thousands of years later, the same basic human needs are still at play when it comes to wayfinding, even if our means of orientation and navigation have changed.

Abraham Maslow is best known for his 1943 paper, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” where he establishes and outlines the five basic human needs. He organized the five principles into a pyramid with each layer relying on the presence of the layer below it.

In design, this pyramid of needs must be taken into account. These needs are the driving forces connecting people to places. When wayfinding or other strategies can help people feel connected to a place, then they feel fulfilled and are more likely to return.

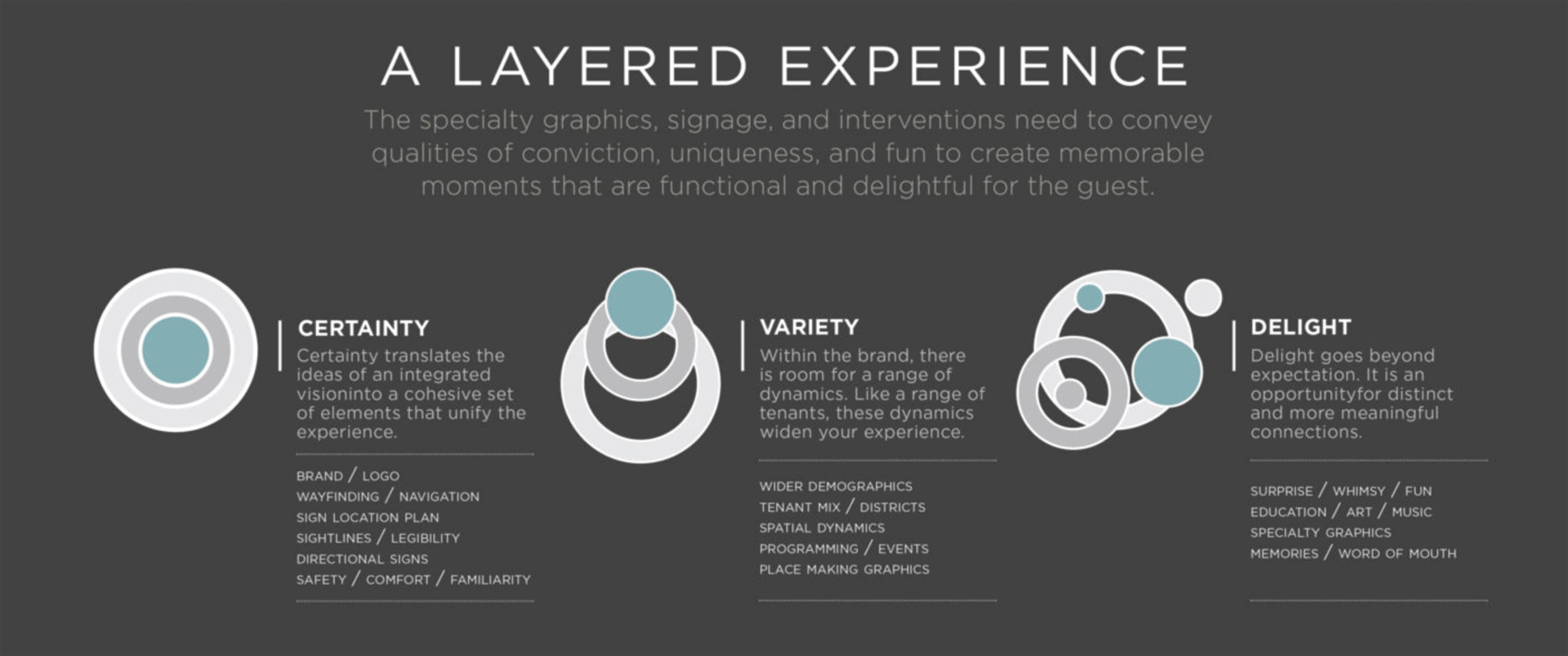

At RSM Design, we have reinterpreted Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in the context of the built environment to help shape our wayfinding definition. We call this framework “Certainty, Variety, and Delight.” It is a way to plan, design, and implement a host of features and elements whose application satisfies all three layers of Maslow’s pyramid.

Certainty Variety Delight. Copyright RSM Design, 2018.

Every day we rely on architecture, signs, landscape, landmarks, lighting, and a host of other cues from the built environment to assure us that, first and foremost, our basic human needs are being addressed. By feeling confident about the safety of our surroundings, we are able to relax. With Certainty, one can let their guard down, begin to decipher the layout of the environment, notice the landmarks and signs, and begin to understand the space.

Many aspects of a project bring Certainty to the experience, such as architecture and lighting. Sign systems, often called wayfinding signage systems, provide a great deal of it. These systems identify uses and direct traffic. Maps, arrows, and labels all provide Certainty. They decipher the environment for the observer.

Once Certainty covers the basic needs, Variety steps in to keep things interesting and begin to address the needs of Maslow’s Psychological layers. Variety may be used to establish the prestige or authenticity of an environment. It can be expressed as shifts in scale, material, color, pattern, or texture. These shifts may denote zones or neighborhoods and serve to break the overall experience into smaller, more human-sized elements.

Features in the Variety classification can add color, visual interest, or meaning to the experience. When used hand in hand with Certainty, Variety also aids in the cognitive mapping of an environment—it is another layer of memory.

The third classification is Delight, which is just that: delightful experiences along the way. These should add to the overall wayfinding experience in more subtle ways. Common examples include art programs, sculptures, and murals.

These points of interest can act as landmarks or come to symbolize a node. They usually inform the personality of the place and often bring with them culture, history, and education.

Maslow’s theory and our application of it to Certainty, Variety, and Delight begin to define wayfinding from a viewpoint of need. This wayfinding definition allows us to effectively answer not only what it is, but also why we need it.

In the 1960s, an educator and urban planner named Kevin Lynch first used the term “wayfinding” in his book, The Image of the City. He describes the city in terms of its physical forms, which he said can be “conveniently classified into five types of elements: paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks.”

In the context of wayfinding, these elements control and facilitate all movement throughout the city for both people and vehicles. While this model is organized around the context and features of a city, it can be applied to most built environments. For example, a shopping mall also has paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks.

When you layer each part of the Kevin Lynch model, you are able to clearly identify logical sign placements.

Paths, Lynch tells us, are “the channels along which the observer customarily, occasionally, or potentially moves. They may be streets, walkways, transit lines, canals, railroads.”

These channels provide the framework for wayfinding as they directly facilitate movement. The success of the design of the paths in a given city heavily affects its overall wayfinding profile.

For instance, Manhattan is an easy to decipher grid. One can easily infer the route necessary to get from 53rd Street to 61st Street. By contrast, the design of the paths in London is not easily decipherable. London’s layout grew organically without an underlying principle, and thus it has a more difficult wayfinding profile.

Edges act in many ways as the counterpoint to paths. The edges of a city are not confined to the perimeter according to Lynch.

Instead, edges “are the boundaries between two phases, linear breaks in continuity; shores, railroad cuts, edges of development, walls.” Edges restrict movement rather than facilitate it, but they find their purpose as organizing elements.

Lynch calls districts “medium-to-large sections of the city, conceived of as having two-dimensional extent, which the observer mentally enters ‘inside of,’ and which are recognizable as having some common, identifying character.”

Districts break the city down into smaller, more digestible pieces. This aids the observer in gaining a better understanding of both the relationship between the pieces and the details within each piece.

In addition, districts provide variety. One part of the city just feels different from the other parts. The transition from one part to the next also provides clues to the observer that can then be used to navigate.

Nodes are essentially intersections or the hubs of a city. Paths lead to nodes and thus they are intrinsically linked to one another.

But nodes can also be more than simply the overlap of paths—they can be the concentration of some use or physical character. Some nodes, Lynch says, can be “the focus and epitome of a district, over which their influence radiates and of which they stand as a symbol.”

Image Credit: Jorge Fernandez Salas on Unsplash

Times Square in Manhattan is a node of the city in which the use has come to define the district. A concentration of theaters created a very competitive environment in which marquees, signs, and now screens vie for the attention of the observer. There is no sign defining the beginning or end of Times Square, but you know whether or not you are in it.

Lynch’s fifth type of element is landmarks. Like districts, landmarks are a point-reference. According to Lynch, “the observer does not enter within them, they are external.”

The Tustin Legacy archway (one of RSM Design's projects) serves as a landmark for the city of Tustin, sitting at over 30′ high.

Landmarks may be grand in scale (such as a mountain or a building) or smaller (like a park or a statue). These consistent clues provide the observer with a reference point from which they can establish their direction or position.

At RSM Design, we use both the Lynch model and Certainty, Variety, and Delight to identify opportunities to intentionally foster and highlight core wayfinding strategies. These models also inform all layers of the experience—not just wayfinding—through the use of color, pattern, texture, language, materiality, signage systems, murals, and sculpture. The clarification of paths, the definition of districts, and the introduction of landmarks are all potential contributions to the overall experience.

An accurate and comprehensive wayfinding definition must account for the fact that wayfinding is more than just signage. Architecture, landscaping, lighting, art, and technology all play a significant role in a wayfinding system. Many decisions impact an environment’s wayfinding profile, such as:

The design of the building and the relationship of the building relative to its surroundings establish the foundation for wayfinding. Sometimes the site and building are so well designed to support intuitive navigation that very little else is needed.

If the architecture is communicating Certainty, then navigation through the space becomes intuitive. With too little Certainty, the wayfinding is hampered and must be supported by signage. Too much Certainty and there is no intrigue—no Variety or Delight. Of course, various project types will require appropriate amounts of Certainty.

Design in architecture, landscape, lighting, and signage should work to meet the needs of an environment and its users together.

Landscape and lighting elements play important roles in providing cues to the observer. They work effortlessly, both individually and in unison, to define paths, identify nodes, and give character to districts.

The landscape design can literally show the way by channeling traffic. The presence (or absence) of light in an environment can communicate the message.

Both landscape and lighting are excellent sources of Certainty, Variety, and Delight, as they use color, shape, and texture to provide cues to the observer. They help translate the architecture in a non-verbal language spoken fluently by humans around the world.

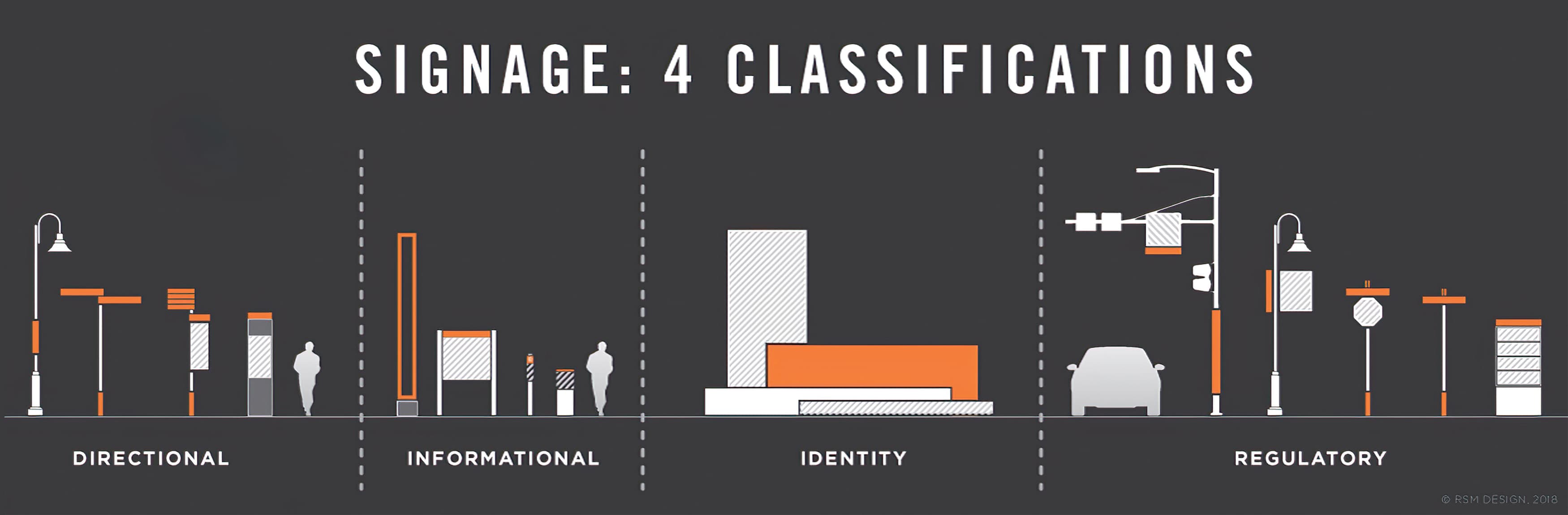

The signage and graphics system is also a vital part of how we define wayfinding. In many cases, signage is the lifeline of a wayfinding system. Buildings gesture, while lighting and landscape enhance and direct, but in complex situations it is usually the signage people look to when uncertainty emerges.

Signage can be broken down into four classifications:

One of Kevin Lynch’s five elements, landmarks, is an often overlooked wayfinding system element. Not quite architecture and not really a sign, landmarks sometimes occur by design and other times by chance.

Maybe some driving need of the architecture creates an abnormality that stands apart visually and, by doing so, is memorable. Perhaps a piece of public art is placed in the project, making that location special and thus memorable.

Lynch cites several characteristics of effective landmarks: “Since the use of landmarks involves the singling out of one element from a host of possibilities, the key characteristic of this class is singularity, some aspect that unique or memorable in the context. Landmarks become more easily identifiable, more likely to be chosen as significant, if they have a clear form, if they contrast with the background, and if there is some prominence of spatial location.”

Some landmarks, like a tower or a spire, can be seen from many vantage points, making them especially useful in helping to orient the observer. The effect of landmarks is powerful, especially to those repeat users of space. Navigation through the use of past experiences and visible landmarks becomes the fastest wayfinding strategy, as the observer no longer must stop or even slow down to read and understand messages on signs.

For more of our thoughts about wayfinding, read our blog post about digital wayfinding and where the industry is headed.

Now that you have a better understanding of what wayfinding is and how we define wayfinding at RSM Design, we hope you will reach out if you are interested in wayfinding services. We believe a collaborative partnership is the best way to discover the unique potential of your environment and bring it to life. If you would like to learn more or start a conversation with our team, please contact us today.