October 08, 2018

It’s Time to Redefine “Architectural Graphic Design”

October 08, 2018

Studying for my architecture undergraduate degree there were countless books that influenced (and continue to influence) my way of thinking about architecture, space, and design… Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (Venturi), For an Architecture of Reality (Benedikt), Towards a New Architecture (Le Corbusier), Silence and Light (Kahn), Invisible Cities (Calvino), In Praise of Shadows (Tanizaki), and so many others.

However, there was one influential book that helped shaped my ability to represent my designs... Architectural Graphics, the classic bestselling reference by Francis D.K. Ching. Originally published in 1974 and now in its sixth edition, it continues to introduce and influence the fundamentals of graphic and design communication. The architectural graphic conventions outlined in the book informed my design process and served as a guide to see a design conveyed and built. Along with the go-to reference book on building design and construction known as the “architect’s bible” or Architectural Graphic Standards (American Institute of Architects, 12th edition) I was all set to branch out into the design profession.

Fast forward a few decades later and I find myself working and creating at an exciting crossroads… the intersection of architecture and graphic design. My attitude and definition of the term architectural graphic design has changed quite a bit since Francis D.K. Ching, and I have found myself redefining what the relationship of architecture and graphics is all about and practicing a different form of architectural graphic design… one that engages the third dimension.

Our studio, RSM Design, was founded in 1997 using the term “environmental graphic design” because we loved seeing how graphic design could shape and influence the physical environment in the built realm, and most importantly how graphics influenced the people using the spaces and making the places. The term “environmental graphic design” has always been an obtuse term and one that is still being defined and ill-defined by many. Over time the use of “environmental” has been referenced more for its ecological and natural uses, rather than the physical setting or surrounding, making it even more difficult to associate environmental with graphics. “No, we do not do ‘green’ sustainable graphics,” I have found myself saying when describing what it is that our studio creates.

While I do not know the reasoning why, I did find it curious when a few years ago the professional organization of the Society of Environmental Graphic Design dropped “environmental” to now become the Society for Experiential Graphic Design. Is this new term any less obtuse than the original? I contend that what our studio is practicing and investigating is how integrated graphic design can symbiotically relate to architecture, hence redefining the term “architectural graphic design.”

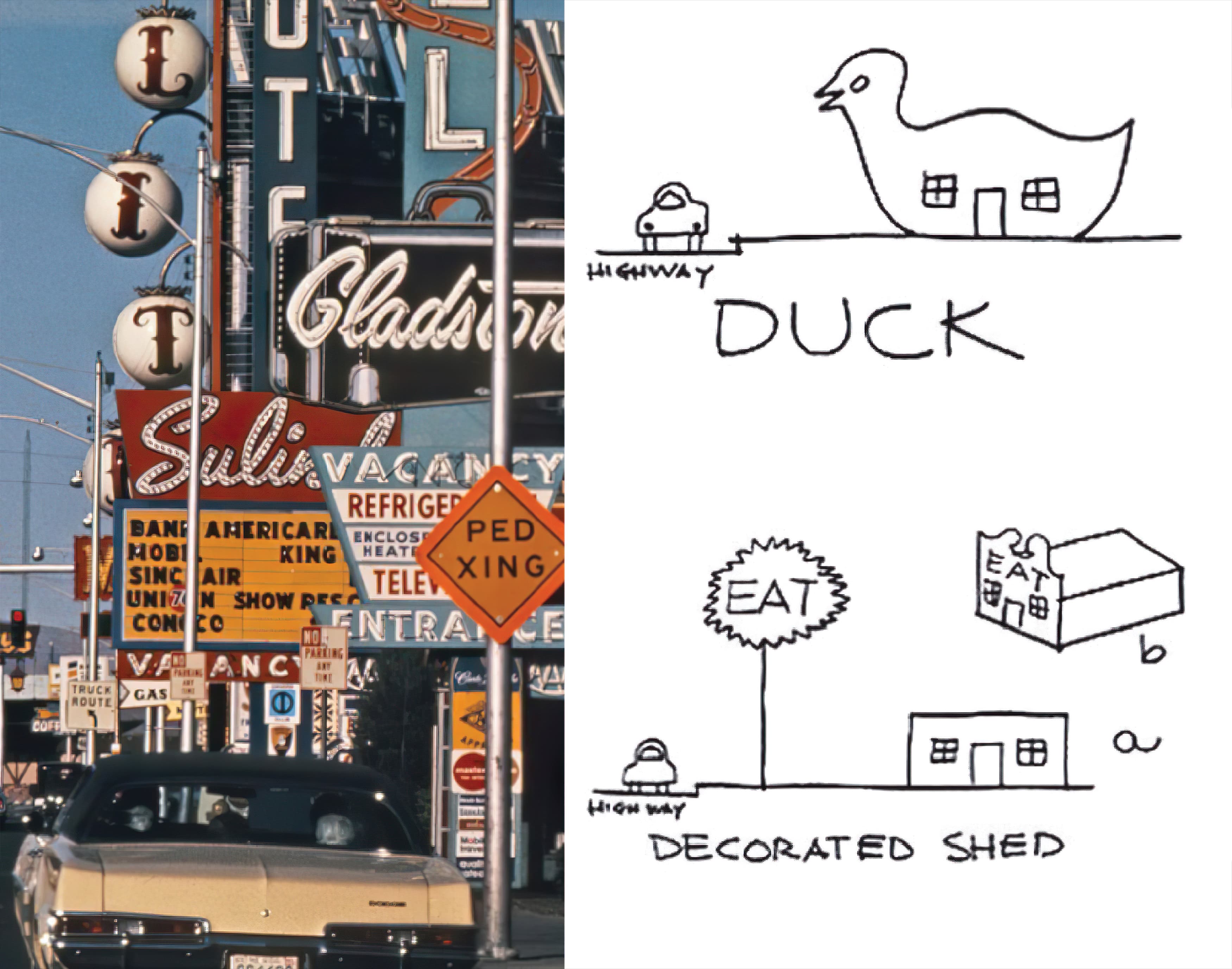

With the recent passing of the influential Robert Venturi, I have again reconsidered the relationship of graphic design and architecture and wanted to understand and redefine how to interpret architectural graphic design. In the book he co-authored with Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour forty-six years ago, Learning from Las Vegas, the “decorated shed” relies on imagery, signage, and graphics to convey its program, in contrast with the “duck” that expresses the program and meaning thru the building’s form. The architectural graphic designs clearly become an integral part of the building’s commercial character and there becomes a new focus on the architecture of the everyday. Today, the commercial character and culture is more powerful and pervasive than ever.

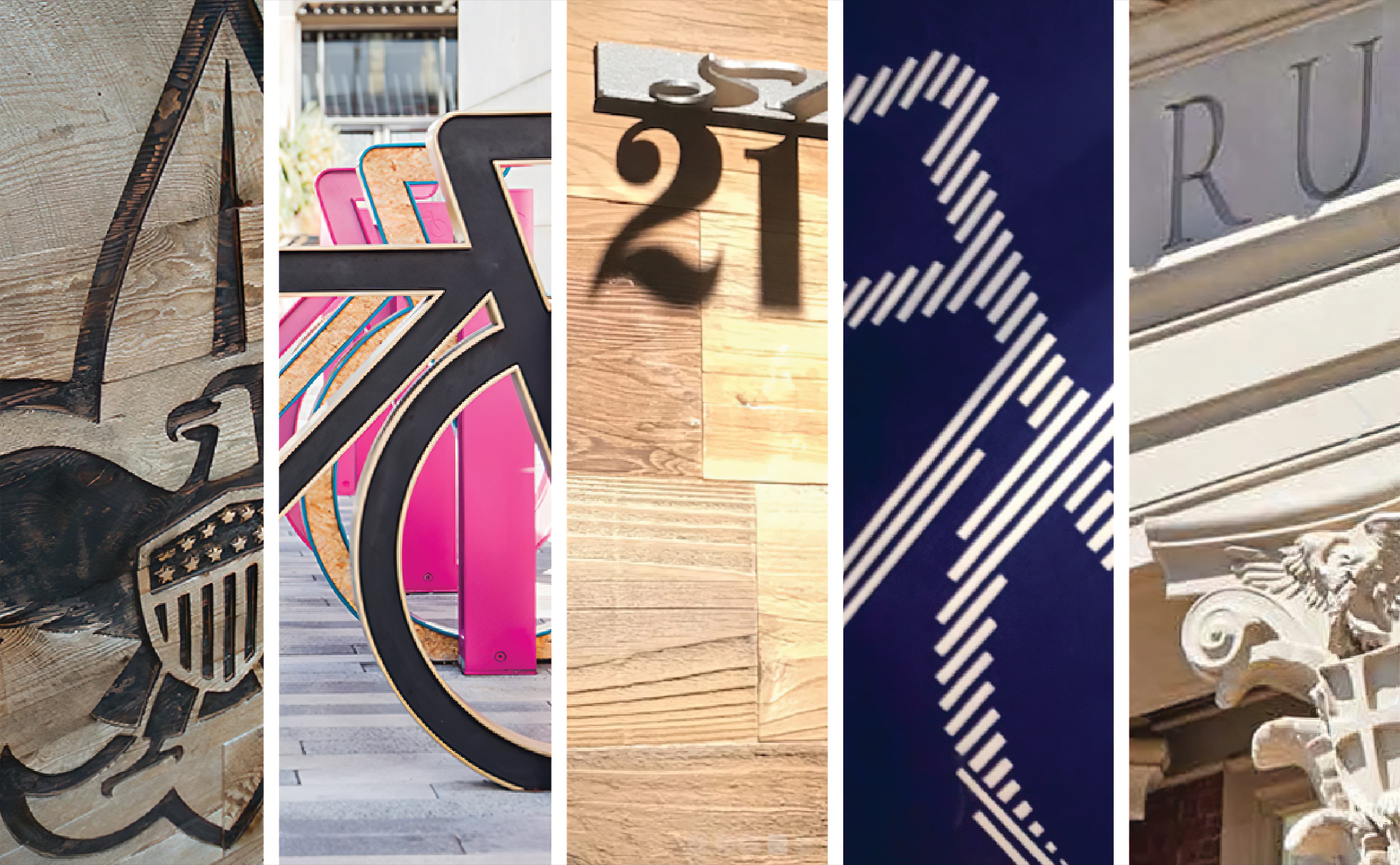

As relevant as commercial architectural graphic design is to buildings and places today, it did not begin with the conversation initiated by Venturi. The disciplines of architecture and graphic design have lived harmoniously and symbiotically together for a long time. Architectural graphic design is not new. It has been around for centuries but only relatively recently have been recognized as an important component of the project narrative. Whether through hieroglyphics, classical inscriptions, façade stenciling (Otto Wagner in Vienna), strong building identities (PSFS Building in Philadelphia), and many other relevant examples, the two disciplines work together to create a cohesive narrative (or “story”) of the building and the way the visitor interacts with it. This marriage is not confined to buildings alone, but also manifests itself in civic spaces and urban places where signage, wayfinding, and art combine to create richness, character, functionality, and engagement.

Architecture speaks of space, form, place, and function while integrated architectural graphic design communicates a building’s function, purpose, message, and narrative. Effective and appropriate architectural graphic designs support the statement made by a building and strengthen its presence. The graphics layered into the conversation derive from the architectural context, spatial context, cultural context, and historical context to which they relate. They are not independent nor superficial. The architectural graphic designs have meaning, form, function, and purpose… similar to the architecture. Whether these architectural graphic designs are woven into the building or space through identity signage, wayfinding signage, specialty features, or graphic embellishments, there is an open dialogue that mutually benefits one another. The inclusion of the architectural graphic designs creates a strong sense of place, fulfills human needs, helps users find their way, and communicates a building’s narrative, fostering a strong conversation between the person and place.

As environments, buildings, and spaces are crafted there are many unique disciplines that play a role in their overall success. The profession’s design process has to be multidisciplinary and collaborative, now more than ever. Important elements such as lighting, mechanical, structural, and landscape need to be joined by architectural graphic design as an equally important layer. The American Institute of Architects has twenty-one Knowledge Communities that work to share information and create connections that advance the profession. It’s time to make architectural graphic design the twenty-second conversation within this community.

So, let’s rethink the relationship of architecture and graphic design and what the term “architectural graphic design” refers to. Move away from the two-dimensional references of architectural representation and weave graphics more deliberately into the vocabulary of the building profession as a necessary component. The relationship of architecture and graphic design should now become a symbiotic and necessary alliance that will orient, inform, and delight. Architectural graphic design can make a difference.